Diagnosing a heart arrhythmia can be a significant challenge. Arrhythmias come and go, and by the time a patient arrives in the emergency room, the feeling of a fluttering or racing heart has often subsided. With that feeling comes misfiring electrical currents, recorded by an ECG, that might offer a cardiologist a clue as to the nature of the problem.

Moore is not a doctor or a nurse. He doesn’t work in a hospital. He’s an electrical engineer at TZ Medical in Portland. In 2009, he helped begin the design process for an in-home cardiac monitor called the Aera CT.

“Several years ago the American Medical Association began to incentivize the development of in-home monitoring products,” Moore explains. By monitoring patients over several weeks, cardiologists were better able to catch and diagnose arrhythmias.

TZ Medical has been around since the early 1990s. Today, its business is based around disposable and, increasingly, electronic medical products, many of which are mainstays in hospitals around the world. Moore was hired in 2008 along with another George Fox alumnus, Reese Wilson (’08), when the company decided to build a new engineering team to develop the next generation of advanced cardiac monitors.

Moore’s first project was designing and developing the Aera CT. “TZ got started with pacemaker monitors back in the ’90s,” Moore says. “The old ones looked like a big red lunch box.”

The “lunch boxes” were transtelephonic pacemaker monitors. If you had an implanted pacemaker in the ’90s, you’d hook yourself up to the machine, dial the number printed on the lid, place your phone into the cradle of the so-called “lunch box,” and then turn off your pacemaker by holding a large magnet over your heart. The monitor would play your heartbeat directly into the phone, with a technician on the other end recording the data using specialized software.

New cardiac monitors are digital. Using solid state memory, they record a patient’s heart rhythm for up to 30 days. If equipped with a cellular modem, that data can be transmitted directly to cardiologists. The device that Moore helped design would eventually become the Aera CT, the first of a new line of advanced cardiac monitors that would generate a significant amount of revenue for the company.

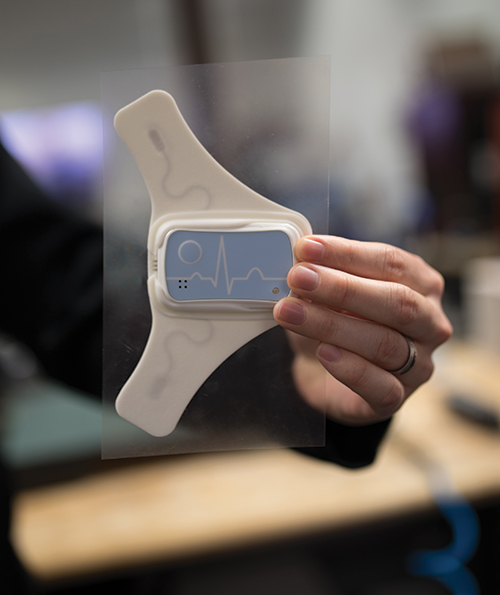

In 2018, TZ Medical will release a small, lightweight cardiac monitor called the Clarus 30. Even with its slender profile the device can record a patient’s heart rhythm for up to seven days.

When he started, TZ Medical had an engineering department of two: Wilson and Moore. “Our deadline was September. We quickly realized that it was way more work than we could handle on our own.”

So Wilson went to his former professors at George Fox and asked for someone who could help them meet their deadline. Chris Hammond (’08), an electrical engineer who had graduated the previous winter, joined the team as an intern in the spring of 2009. By September, the first prototype for the Aera CT was finished and Hammond had a full-time job.

With the release of the Aera CT, the company’s annual revenue swelled from $9 million to $14 million a year. “As it turned out there was just as much, if not more, mechanical engineering than electrical engineering to do,” Moore says. “And probably even more programming.”

With the budget to begin building an engineering team, Moore went back to the professors at George Fox and asked for another recommendation. In 2013, he hired Mike Morrison (’13), a mechanical engineer.

Before releasing the latest version of a product, engineers at TZ Medical test firmware changes in the updated device using simulated ECG signals. Here, an engineer tests the Clarus 40M cardiac monitor.

Pleased with the results he was getting from the engineers hired from his alma mater, Moore has gone back, again and again, looking for new talent. With the exception of 2010, TZ Medical has hired a new engineer, all George Fox graduates, every year since 2008. In 2015, the company hired Mike Morrison’s brother Greg (’15), also a mechanical engineer, and in 2016 they recruited computer engineer Dieter Mueller (’16). In 2017, they hired another computer engineer, Drew Camp (’17), added computer science graduate Chase Atkinson (’17), and took on an intern, Austin Ziegler, who will join the TZ Medical engineering team full time after he graduates in the spring. In all, 13 George Fox graduates have held full-time positions or internships with the company. Five, including Wilson, have moved on to other opportunities.

“It’s turned into a bit of a dynasty here at TZ,” says Moore. All of them laugh when they hear it, but it’s only half joke. Six George Fox engineers make up the entire product development team for a $14-million-a-year company with more than 50 employees, not to mention Atkinson in the computer science department and intern Ziegler.

By hiring so many George Fox graduates, the engineers at TZ Medical are in a unique position to provide feedback to the engineering department. “We end up going to professors and making suggestions,” Hammond says.

By offering their suggestions about the curriculum, Hammond hopes his alma mater can graduate increasingly competitive engineering classes. Likewise, the influx of George Fox graduates has resulted in an engineering team that is focused on helping people – not just the bottom line.

That, they all agree, is one of the most appealing parts of working at TZ Medical.

“We all love being able to actually make a difference in the projects we’re working on,” Hammond says.

Able to record a patient’s heart rhythm for up to 30 days, the Clarus 40M can also detect common arrhythmias and wirelessly transmit that information to medical staff.

And, as the company has grown, the engineering department has been given more and more autonomy to do just that, moving from a management structure where two or three engineers report to the president, to a self-directed engineering team that is run internally.

“We have almost full control over the whole design process within the constraints of regulatory compliance,” Moore says. “It’s an exciting place to work for a new engineer because of how much design you get to do.”

For all their autonomy, the engineers are quick to point out that many of their most innovative ideas were prompted by the doctors, nurses and lab technicians that TZ serves. “TZ has always been designed around partnering with customers,” Moore says. “They’re the ones working in the field, and they’re the ones who can identify a problem.”

The Adjustable Radial Cuff, set to be released in 2018, uses a small hand pump and inflatable bladder to apply pressure and stop bleeding after a transradial procedure. It was developed at the urging of a lab technician, who once manually applied pressure to a patient’s radial artery for four hours following an operation.

A technician in a cath lab, for example, came to the TZ engineers in need of a device that would support his patients’ arms during catheterization and keep them from falling off the tables. His need turned into an entire line of padded polycarbonate supports that TZ Medical now markets as Comfort Zone.

When Greg Morrison joined TZ in 2015, the product the company offered was little more than a zip tie. The engineers knew they could improve it.

“The very first prototype was a fix intended for the old band,” Morrison says. “I went through three or four versions before I decided to scrap it and go with something new.”

Based on feedback from hospital staff, the new design needed to apply pressure more precisely and it needed to be more comfortable.

Beside his desk, Morrison has a cardboard box full of abandoned prototypes. Digging through it, he remembers exactly where an idea began to take shape. The latest iteration is an adjustable radial arm band with a built-in pad for comfort. It is, unequivocally, better than a zip tie.

“I think this is version 56,” Morrison says, laughing. “I started on this basically when I started here, which was three years ago. We’re very close to releasing, but the last 5 percent just takes forever.”

All the engineers agree that one of the great joys in their work is to start with nothing more than an idea and then, later, to hold the thing itself in hand.

“It’s so satisfying to know a device that well,” Morrison says as he examines the nearly finished product.

He pointed out a small curved face to make his point. “It took me forever to figure out how to make all of the faces match up,” he says. “I know exactly how it’s formed. No one thinks about that.”

Regardless of the device in question, any discussion with the engineers at TZ Medical will eventually find its way back to their process, which always starts with the people they’re serving.

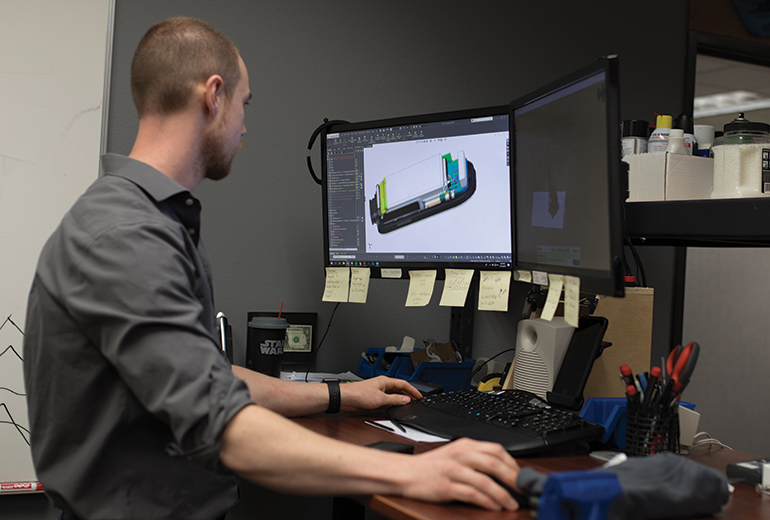

Mike Morrison examines a “solid model” of the Clarus cardiac monitor’s internal components on his computer. An embedded device like this one requires extensive collaboration between engineers and component manufacturers, regulatory bodies and vendors in order to ensure a high degree of quality and precision.

By improving the processes within the hospitals, Moore added, an engineer is also improving the outcomes of their patients.

“This is something that I really value,” Hammond says. “I like the idea behind it: How do we as engineers do service? How do we use the skills God has given us to actually make a difference? The answer, it turns out, is find a job that makes a difference, and then do your job.”

With the connection between George Fox and TZ Medical firmly established, this year the company is sponsoring two senior design projects. One project is being led by intern Ziegler, whose team is designing a small LED that can be adhered to a surgical retractor to help light the areas of an operation site that aren’t illuminated by overhead lamps.

“It was something that we wanted to do at some point,” Hammond says, “so we just handed it off to Austin’s team.” The team has committed to delivering not just a concept or a prototype, but 1,000 manufactured pieces by the end of the spring semester.

“It’s not a normal senior assignment,” Hammond says. “But when they get this thing done and they’ve graduated, they can say they’ve designed a Class 1 medical device that is on the market. It’s going to be a powerful portfolio piece.”

TZ’s approach has even found traction in the Servant Engineering Program, a staple of any engineering major’s junior-year course load where students develop technical solutions for organizations focused on serving others. It’s hard to say whether George Fox engineers are succeeding at TZ Medical because of the model of service provided at George Fox, or the other way around. But Moore isn’t interested in chicken-or-the-egg questions.

“It’s just cool to see that approach being validated,” Moore says, “to see the human aspect factoring in.”